Barkha Dutt

A judge who tried the case acquitted the accused because he believed men of a certain caste would not ‘touch’ a woman of a caste considered inferior to theirs; forgetting, again that Rape is Not about Sex; it’s about Power, says Barkha Dutt.

Dear colleagues,

Before we talk about what the most sensitive and appropriate way there might be for all of us to report on rape and sexual abuse, we should first acknowledge how long it took all of us — women journalists included, and sometimes especially us women — to place the issue at the top of the news hierarchy. I can confess that when I first began my job as a twenty-something I was very defensive about being saddled with covering what were then called ‘women’s features’. I wanted to report on politics, insurgency, riots, war, calamities — what I thought was the ‘tough’ stuff that wouldn’t ‘gender’ me as a ‘female’ reporter.

Among my earliest assignments though was the gang rape of a Dalit woman — Bhanwari Devi — in a village in Rajasthan, who had been assaulted for trying to stop the child marriage of a one-year-old infant. She worked with a government program that sought to create local awareness against this retrograde custom. The rapists included the father of the child. If that was not bone-chilling enough; a judge who tried the case acquitted the accused because he believed men of a certain caste would not ‘touch’ a woman of a caste considered inferior to theirs; forgetting, again that Rape is Not about Sex; it’s about Power. Bhanwari Devi was ostracised by the village for daring to complain against the perpetrators. She lived on the outskirts of her own village, shunned at weddings and funerals and forbidden to draw water from the common well. That first assignment taught me swiftly that there is nothing ‘soft’ about reporting violence against women; it remains mired in our country’s deepest fault lines — caste and class.

But in 2016, the story of Bhanwari Devi brings home some new and critical questions for me as a journalist. Our collective reportage on the ‘Nirbhaya’ case (the horrific gang rape of Jyoti Singh, a young medical student in Delhi) and the mass student protests that followed it pressured Parliament to change the laws and finally made sexual violence a lead story that could no longer be buried in the inside pages. But I have always wondered why we never responded to Bhanwari Devi with the same intensity as we did to Nirbhaya. The year that the Nirbhaya case made international headlines was also the 20th year that Bhanwari Devi had been fighting a hostile system for justice. Ironically, it is to Bhanwari Devi that we owe the ‘Vishakha’ guidelines — the first legal sexual harassment code that is now required to be followed by all workplaces. The Supreme Court recognised that Bhanwari had been abused while doing her job. It is because of Bhanwari and these guidelines her battle gifted us that influential men like RK Pachauri or Tarun Tejpal are facing trial. Yet, her own story is now on the margins of public attention as is the fact that the men who did this to her have still not been punished. More than two decades later there is still no verdict in her case. So why is our outrage missing? Is it because we are guilty of fickleness, moving on from one headline to the next? Or is it because our coverage of rape betrays the worst sort of (subliminal) class bias?

Did ‘Nirbhaya’ get our attention in a way Bhanwari did not because one was the story of aspirational India set in an identifiable urban setting and the other was the suffering of a marginalised woman, the injustice to her as a woman clearly compounded by the caste bigotry against her. The Nirbhaya case was an inflection point in how we talk about rape and not one of us can ever shake off the thought of that moving bus and an iron rod being forced into the private parts of a young woman coming home from watching a movie. I will never undermine the enormity of that case; but I often wonder what it says about us that others like Bhanwari Devi don’t get an equal amount of anger and attention.

Apart from our transitory and selective focus there is a trivialisation that is creeping into our media conversations about rape that is disturbing. Take a recent ‘sex’ tape for example on the assignations of a Delhi minister. What first appeared to be consensual sex between adults has subsequently been registered as a case of rape but not before a tawdry, albeit censored camera recording played out on several TV channels. There are legitimate questions about whether the minister (since sacked) misused the power of public office to coerce the woman who is also on tape. However, the looping of this sordid footage that played endlessly to satisfy the vicarious curiosity of a mass audience surely undermines the gravity of an offence like rape. Salacious sensationalism can only do disservice to a conversation that we as a people have only just begun to have. The National Commission for Women then summoning an Aam Aadmi Party representative for writing a skeptical column (importantly at a time when there was no known complaint of rape) on the tapes and way his own party responded further eroded the seriousness of the debate.

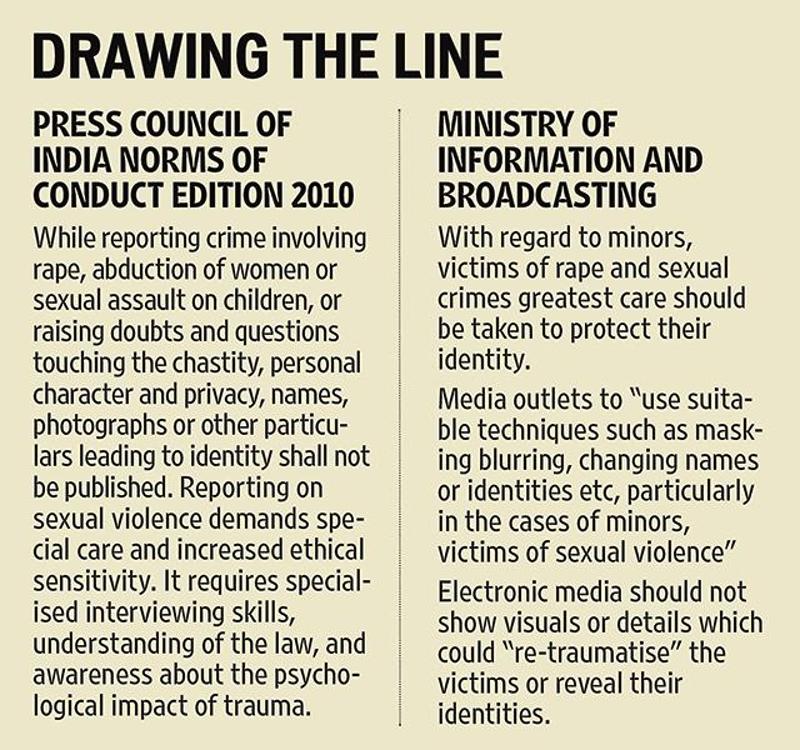

Finally, we must discourage language that links rape to honour. In the aftermath of every such assault aggrieved families, politicians and lawyers will often use words that confuse notions of respect. When women fight back, it is suggested they are fighting for their honour; their self-respect. The rapist and his crime cannot be allowed to define a woman’s sense of self. The fight is for justice; the dishonour is that of the criminal. And though finding that balance is always precarious, we must look for ways to report the monstrosity of the crime without violating the privacy of the rape survivor or her family with intrusive questions and thrusting microphones. We must allow the women or their families (or young men who have experienced sexual abuse as boys) to choose their own pace, their own language and give them the freedom to draw their own red lines. They cannot and must not be pushed by the punishing and often insensitive deadlines of the next television bulletin or next morning’s newspaper.

Rape is not a spectacle. Rape is not a first headline only when it’s absolutely macabre or when it happens identifiably to people like us. Never forget – most women in India get abused within the circle of trust; 90% of Indian women who have been sexually abused know their aggressor. And we haven’t even begun talking about marital rape yet. Rape and sexual violence — they’re closer home than we think.

(The author is consulting editor, NDTV, and founding member, Ideas Collective)